Business Bytes Women's History Month Special: Papad Power

Welcome to Business Bytes’ first edition for the Spring semester!

You’ve probably heard about the story behind Amul, India’s most famous dairy co-operative. Today’s story is about another famous Indian co-operative, with equally humble origins.

(In case you already know the ins and outs of this fantastic story, feel free to scroll down below for a really cool recommendation on a fictional AI tale.)

Read on to know more about India’s biggest papad co-operative, and the wonderful women behind it!

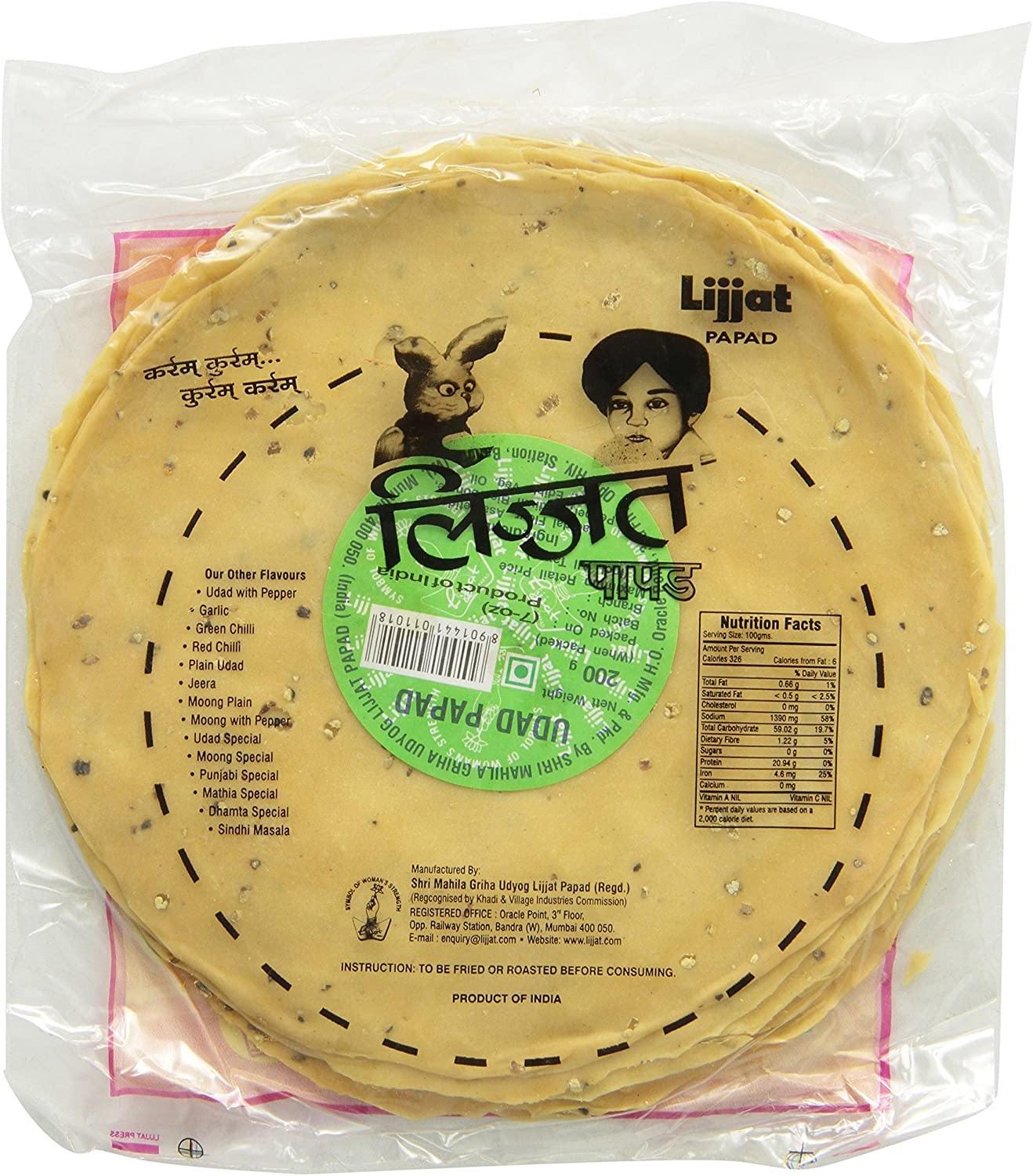

Does this packet look familiar to you?

Today’s story is about papad (or papadam). You’ve probably heard of it. It’s the thing they serve with khichdi. And if you’re like me, it’s the first thing you order at an Indian restaurant (masala papad, anyone?). Regardless of which kind of papad you like — aloo, rice, pani puri flavoured, or something else, chances are you’ve had Lijjat Papad at least once — it’s the market leader in the organised papad market, with a whopping 60 percent market share.

Your parents probably told you the story of the “seven sisters” and how they started making papad on the terrace of their building seven times already. But if you haven’t heard of them - this story is for you. (Besides, it doesn’t hurt to retell an old story and keep it alive in the public imagination, does it?)

On Sunday, 15 March 1969, seven Gujarati women from Bombay - Jaswantiben Jamnadas Popat, Parvatiben Ramdas Thodani, Ujamben Narandas Kundalia, Banuben. N. Tanna, Laguben Amritlal Gokani, Jayaben V. Vithalani, and Diwaliben Lukka, got together and rolled four packets of papad to sell.

“We were semi-literate which restricted our chances to get jobs. But we realised our papad-making expertise could be used to earn small amounts of money to help our husbands reduce their financial responsibility," said Mrs. Jaswanti Popat in an interview with BBC India.

So how did seven semi-literate women build an organisation that went from having ₹80 (₹6,800 adjusting for inflation) in seed capital to the largest papad business in the country, with a $100m turnover, 40,000 workers and exports to the Middle East, Europe, East Asia and the US?

According to Mrs, Jaswanti Popat, the organisation was never meant to become that big — but their papads sold fast, and they paid back the ₹80 loan in just 15 days. Eventually, more women joined the venture. And instead of renting out some sort of large warehouse to accommodate the increased workforce, it was decided that freshly kneaded dough would be supplied to the members so that they could roll the papads at home. The finished products would be brought the next day, tested, weighed, and packed for delivery - a procedure that is followed even today.

The name “Lijjat” which means “tasty” was crowdsourced (or is that word only used for when you use the internet?) through a contest with a prize money of ₹5.

Initially the group gained publicity through word of mouth and articles in vernacular newspapers, but in the 1980s, they started taking part in trade fairs and exhibitions, which greatly increased their visibility. They also put out advertisment featuring a puppet, which became hugely popular and was shown on Indian television channels as late as 2008.

So what is their business model? How do they scale, operate, and empower women? What gives the papads power?

For starters, the Shri Griha Mahila Udyog Lijjat Papad (yes, that’s the full name) never accept donations, even if they incur losses.

The following excerpt from an article in The Hindu Business Line provides a good overview of their procedure:

Any woman above the age of 18 (irrespective of caste, religion or colour) who wants to roll papads can approach a Lijjat office, sign the pledge and become a sister-member or behn . No one is turned away (It is a mystery to market watchers as to how the organisation, instead of collapsing under the weight of the growing workforce, continues to gain in strength).

After training, she can choose a sphere of work she is comfortable in — kneading the dough; rolling papads; weighing; packing; printing. The work environment is non-competitive. Each woman is paid on a daily basis for the work done and profits are shared equally. Every behn has the opportunity to rise from the lowest level to the highest ranks in the organisational structure. There is no retirement age, but anyone can voluntarily leave the organisation.

Men can be salaried employees but have no part in the profits or in the decision-making process.

Twenty-one members, chosen by consensus, run the organisation. Sanchalikas or branch heads manage branches. Office-bearers meet regularly to coordinate activities at the State and national level. All branches are autonomous, and handle marketing and profit distribution among the behns.

Moreover, the business is run as a non-profit - dealers get 7% commission, 2% of turnover is retained for organisational expenditure, and the rest is distributed among the behns thrice a year in the form of cash or gold.

Lijjat Papad also runs literacy and computer education programs for members and their families and give scholarships “Chhaganbapa Smruti Scholarships” to the daughters of their members, in addition to a lot of other social programs such as blood donation drives.

In 2021, Mrs. Jaswanti Popat, the only surviving member of the original septet, was awarded the Padma Sri for “Trade and Industry.”

In an era where highly educated, accomplished women still face obstacles along the way to starting their ventures, let us take this opportunity to truly appreciate the magnitude of the achievement of seven semi-literate women in the 1950s who grew as organically as the word permits, never compromised on their principles, and provided thousands of women and their families with a stable source of income and support.

Maybe think about that the next time you bite into a papad at the mess hall.

Here’s an interesting read we discovered yesterday.

This article / story is so cool, we’ll let it speak for itself:

The year is 2028, and this is Turing Test!, the game show that separates man from machine! Our star tonight is Dr. Andrea Mann, a generative linguist at University of California, Berkeley. She’ll face five hidden contestants, code-named Earth, Water, Air, Fire, and Spirit. One will be a human telling the truth about their humanity. One will be a human pretending to be an AI. One will be an AI telling the truth about their artificiality. One will be an AI pretending to be human. And one will be a total wild card. Dr. Mann, you have one hour, starting now.

MANN: All right. My first question is for Earth. Tell me about yourself.

Head on to the official Substack to read it!

We’re launching a podcast!

Ashoka Business Review is launching its very own podcast - stay tuned for insightful takes on the business world from some of your favourite professors and industry professionals!

Follow our socials (@ashokabusinessclub on Instagram) for more updates.